A Great Life with a Tragic Ending

Few people know the story of Vera Menchik yet it deserves to be told. She was the first women’s world chess champion in 1927 and retained the title undefeated until her untimely death at the age of 38 in 1944 during a rocket attack on London. She is more properly compared with the great male players of her era against whom she scored creditably. The absence of a full biography of Vera in English reflects the peculiar circumstances of her life and death.

Vera was, in modern terminology, a refugee and essentially a stateless person for much of her life. She was born in Moscow in 1906 during the period of the Russian Empire to an expatriate family who was forced to flee when she was 15 following the Russian Revolution having lost their livelihood. As they passed through Europe, her father and mother split up in his homeland Czechoslovakia which had been created out of the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian empire. She arrived in England and took up residence in the seaside town of Hastings. (The fact that Hastings had hosted the world’s longest series of annual chess tournaments since 1895 was a happy coincidence.) Vera never attained British nationality until near the end of her life even though she had been domiciled in England from 1921. She won the first-ever Women’s World Championships held in London in 1927 under a Russian flag; thereafter she nominally represented Czechoslovakia until finally she represented England in 1939 following her marriage to a senior official within the British Chess Federation.

Vera’s grandfather was Arthur Illingworth, a wealthy trader from Lancashire who had set up business in Moscow where his Anglo-Russian daughter Olga married František Menčik, a successful estate manager. Vera learned chess from her father and performed well at school. Her younger sister Olga was also a good chess player and the sisters remained close throughout their lives.

Vera was a woman in a man’s world – she had to struggle harder to achieve the kind of recognition which was accorded to men. She appeared like a comet in the sky and it would be many years until other women were able to reach her level. At her first major international tournament at Karlsbad in 1929, she was the only female participant in a tournament of 22 great players. Even as women’s world champion, some of the male players objected to her participation. The Viennese master Albert Becker joked that anybody who lost to her should belong to the Vera Menchik Club. By an irony of history, he became its first member losing to her in the third round. She beat many other grandmasters during her career including the Dutchman Max Euwe in 1930 and 1931 (both at Hastings) who was to become world champion in 1935.

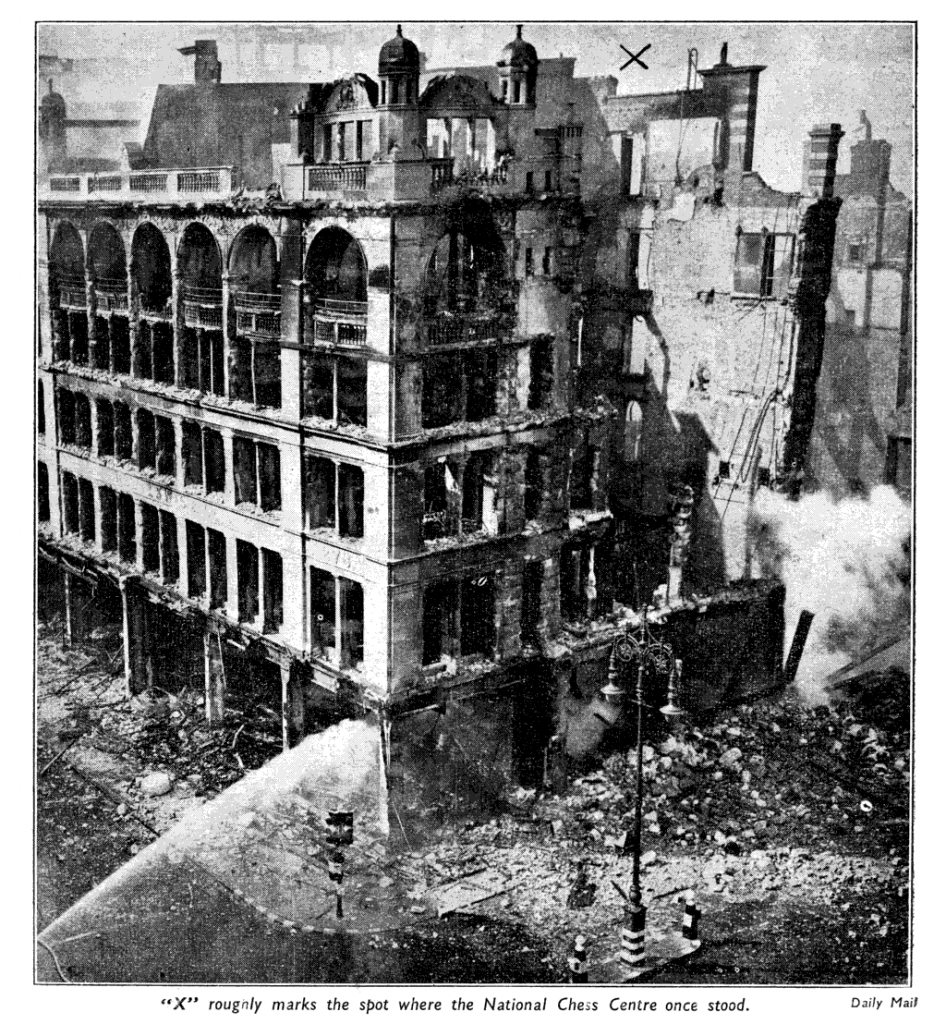

Although she is often portrayed as being Russian or Czech (Věra Menčková ) or latterly British, she was a true cosmopolitan. She knew that life could be unstable in any country. She had lived through the Russian Revolution; one parent was left behind in Czechoslovakia; she had moved westwards across Europe and embraced different cultures and languages at formative stages of her life. It is no wonder that she learned also to speak Esperanto which was designated to be the world’s lingua franca before English achieved its dominance. As a leading chess player, she traveled back to Moscow and to Czechoslovakia several times as well as to South America for her final match to retain the women’s world champion title in 1939. She needed to be self-sufficient and obtained roles as the games editor of a chess magazine as well as being appointed the manager of the National Chess Centre in Oxford Street which was destroyed during the Blitz in 1940.

Vera survived the attack on the Chess Centre and most of the war. After her husband died, she moved in with her mother and sister to a house in south London. They took the precaution of going down to the cellar during bombing raids. Tragically the house received a direct hit from a flying bomb in 1944 and the entire family was wiped out. Hardly any of her possessions remained save for one dented trophy. The records at the national chess centre were destroyed as were her personal effects including her chess memorabilia. At least there remains a record of the moves played in her games which serve as testimony to her remarkable career as not only the first women’s world chess champion but also a woman who broke boundaries wherever she went and demonstrated that a woman is capable of standing on her own feet professionally and leading a full and eventful life.

For more details go to British Chess News